Tipitaka Studies 2: The Veranja Crisis – From Famine to the Genesis of Monastic Discipline for Sustainability

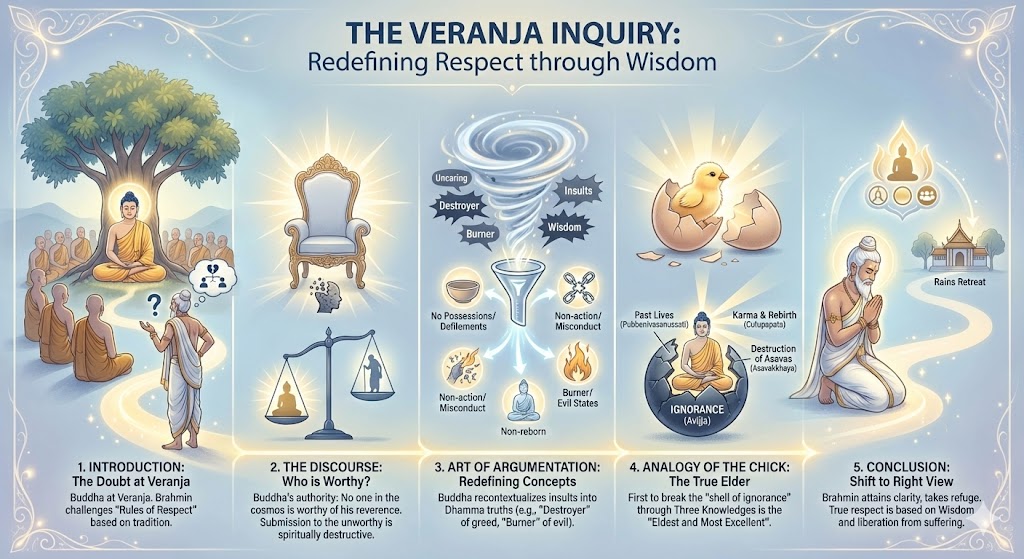

Introduction: The Paradox at Veranja

After the “Veranja Brahmin” surrendered his pride and professed himself as a lay follower (Upasaka), he invited the Blessed One, along with a large company of approximately 500 monks, to observe the Rains Retreat (Vassa) at the city of Veranja. This event initially appeared to be a promising omen for the propagation of the Dhamma. However, contrary to expectations, that rainy season turned into one of the most significant trials in the history of the Buddha’s ministry. The city of Veranja faced a severe “Famine” (Dubbhikkha), leading to profound debates concerning the use of supernatural powers versus the establishment of a foundation for the Buddhist order’s sustainability.

1. Scarcity and Monastic Decorum (Samanasarupa)

During that period, Veranja’s economy collapsed to its lowest point. The populace struggled for survival to such an extent that the Vinaya Pitaka records the sight of “white bones scattered,” and food distribution had to be managed through a rationing system (Salaka). Consequently, the monks could not go on alms rounds (Pindapata) to sustain themselves as usual.

However, the survival of the Sangha was made possible through the benevolence of a group of 500 “horse merchants” from the Northern Path (Uttarapatha) who were camping in the area. These merchants shared “red rice” (steamed coarse rice intended for horses), offering about one measure (pattha) to each monk. The monks had to take this horse fodder and pound it in a mortar to make it edible. Even Venerable Ananda, the Buddha’s attendant, had to grind this red rice on a stone slab to offer to the Blessed One.

The incident where the Buddha heard the sound of the mortars and praised the monks, saying, “It is well, monks. You have won a special victory,” reflects a profound philosophy: even in the most dire times, maintaining mental fortitude, scraping away defilements, and not becoming slaves to hunger (Craving) constitutes the true victory of a recluse.

2. The Relationship between Supernatural Miracles and Buddhist Ethics

Amidst this crisis, Venerable Maha Moggallana, the foremost in psychic powers, approached the Buddha to propose two supernatural solutions to alleviate the suffering:

- Overturning the Earth: To access the “essence of the earth” (nutritious soil) beneath, which was as sweet as honeycomb, for the monks to eat.

- Intercontinental Alms Round: To transport the entire Sangha via psychic power to seek alms in the continent of Uttarakuru.

The Buddha rejected both proposals based on ethical grounds and pragmatism:

- Ethical Concern: Overturning the earth would harm the living beings dwelling upon and within it, contradicting the principle of Metta (Loving-kindness) and potentially causing confusion or disaster for those beings.

- Equality and Practicality: If psychic powers were used to transport the group, those monks without psychic powers would be left behind, unable to follow.

This case demonstrates that in Buddhism, “Wisdom and Great Compassion” always supersede “Supernatural Powers.” Any solution to a problem must consider the impact on others and the practical feasibility for the community as a whole.

3. The Thread of Vinaya: The Philosophy of Religious Sustainability

During the quietude of the retreat, Venerable Sariputta entered solitary meditation and reflected on why the Dispensations (Sasana) of some past Buddhas lasted a long time, while others perished quickly.

The Buddha answered using the “Analogy of the Thread and Flowers”:

- Unsustainable Dispensations: Likened to loose flowers piled on a plank without a thread to hold them together. When the wind blows, the flowers are scattered and destroyed. (This occurs when the Buddha does not preach the Dhamma in detail and does not promulgate the Vinaya/Rules).

- Sustainable Dispensations: Likened to flowers that are well-strung together with a thread; the wind cannot scatter them. (This is achieved through the promulgation of the Vinaya and the recitation of the Patimokkha).

4. Buddhist Jurisprudence: The Timing of Legislation

When Venerable Sariputta requested the Buddha to immediately promulgate the Training Rules (Sikkhapada) to ensure the stability of the religion, the Buddha held him back. He reasoned, based on spiritual jurisprudence, that rules or disciplinary codes should only be enacted when “Asavatthaniya Dhamma” (Conditions leading to the influx of taints or fermentations) appear within the Sangha. These conditions typically arise when:

- The Sangha has become great by long standing/seniority (Rattannu-mahatta).

- The Sangha has become great by extension/numbers (Vepulla-mahatta).

- The Sangha has become great by gain (Labhagga-mahatta).

At that time (during the Veranja retreat), the Sangha was still pure and free from corruption—even the monk with the lowest attainment was a Stream-enterer (Sotapanna). Therefore, it was not yet the appropriate time to enact legislation.

Conclusion

The Rains Retreat at Veranja was not merely a story of endurance against starvation. It was a historical turning point that showcased critical transitions: from handling crises with Wisdom to rejecting supernatural quick fixes, and finally, crystallizing the concept of “Vinaya as the Thread of Sustainability.” This established the Monastic Code as the core mechanism for maintaining the stability of Buddhism for generations to come.